I have written four books on military history, three of which focus on how the British army was supplied in the two world wars. My most recent books explore the story of British manufacturing which played such a massive part in those wars.

Vehicles to Vaccines

The book is a quest to discover what happened to British manufacturing in the decades after the Second World War. People say that we don’t make things any more. Is this true?

I try to answer this question by exploring what happened in manufacturing sectors and to major manufacturing companies. I seek out manufacturing heroes, and try to map out where we are as the twenty-first century gets underway.

In 1951, the Festival of Britain was celebrating British manufacturing; we built ships, wonderful aircraft like the Viscount and cars a plenty. Seventy years later a British company and a British University teamed up to produce a vaccine that saved thousands of lives from Covid.

It has been a period of astonishing change, from a third of the working population employed in manufacturing to now just one tenth. Britain now ranks eighth among the world’s top manufacturing nations.

This book seeks to explore what has changed: the story of British manufacturing from steam trains to semiconductors; from cotton mills to 3D printing; from ocean liners to satellites.

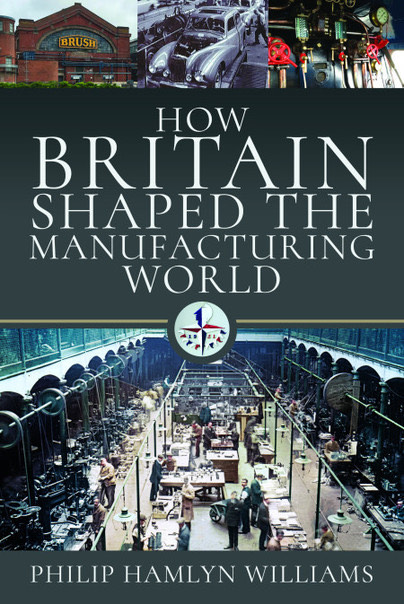

How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World

The peoples of the British Isles gave to the world the foundations on which modern manufacturing economies are built. This is quite an assertion, but history shows that, in the late eighteenth century, a remarkable combination of factors and circumstances combined to give birth to Britain as the first manufacturing nation. Further factors allowed it to remain top manufacturing dog well into the twentieth century whilst other countries were busy playing catch- up. Through two world wars and the surrounding years, British manufacturing remained strong, albeit whilst ceding the lead to the United States.

This book seeks to tell the remarkable story of British manufacturing, using the Great Exhibition of 1851 as a prism. Prince Albert and Sir Henry Cole had conceived an idea of bringing together exhibits from manufacturers across the world to show to its many millions of visitors the pre-eminence of the British. 1851 was not the start, but rather a pause for a bask in glory.

The book traces back from the exhibits in Hyde Park’s Crystal Palace to identify the factors that gave rise to this pre-eminence, just as the factory system at Cromford Mill. It then follows developments up until the Festival of Britain exactly one century later. Steam power and communication by electric telegraph, both British inventions, predated the Exhibition. After it came the sewing machine and bicycle, motor car and aeroplane, but also electrical power, radio and the chemical and pharmaceutical industries.

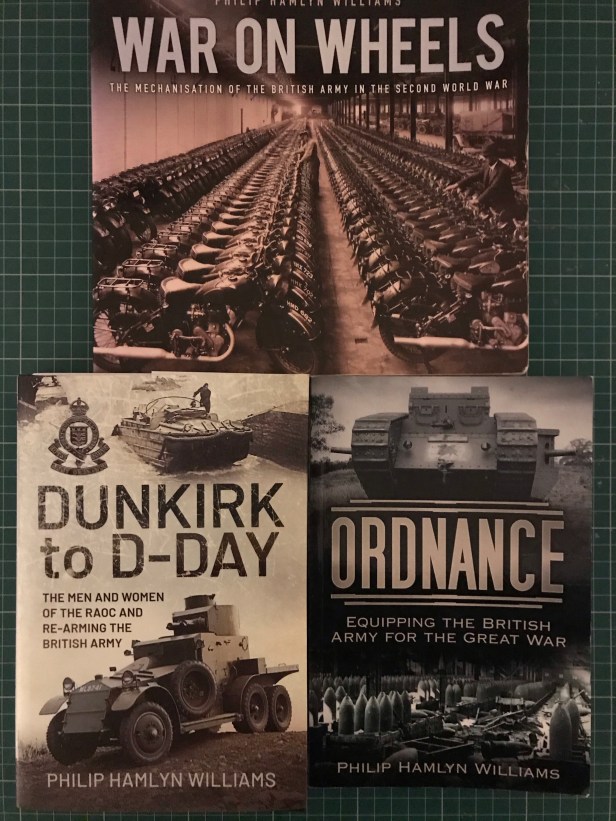

War on Wheels

‘To almost every man of the Allied Armies, the predominant memory of the campaign, beyond the horror of battle, was the astounding efficiency of the supply services’ Max Hastings in Overlord

During the Second World War the British Army underwent a complete transformation as the number of vehicles grew from 40,000 to 1.5 million, ranging from tanks and giant tank transporters to jeeps, mobile baths and offices, and scout cars. At the same time the way in which the army was provided with all it needed was transformed – arms and ammunition, radio, clothing and places to sleep and wash.

In this fascinating volume, Philip Hamlyn Williams makes extensive use of archival material and first-hand accounts to follow some of the men and women who mechanised the British Army from the early days at Chilwell near Nottingham, through the near disaster of the BEF, Desert War and Italian invasion, to preparations for D-Day and war in the Far East. Stunningly illustrated throughout, War on Wheels explores the building of the network of massive depots across the UK and throughout the theatres of war that, with creative input from the UK motor industry, supplied the British Army. It is truly an impressive work to be enjoyed by anyone intrigued by the machines and logistics of the British Army in the Second World War.

Ordnance

Kitchener’s ‘Contemptible Little Army’ which crossed to France in August 1914 was highly professional, but was small and equipped only with what it could carry. Facing it was a force of continental proportions, heavily armed and well supplied. The task of equipping the British Army, which would grow out of all recognition, was truly herculean.

It was, though, undertaken by ordinary men and women all around the British Isles and beyond. Men fit to fight in the trenches had been called to the colours do just that, so it was largely those left behind. In time government recognised the need for skills of engineering and logistics and such who had survived the onslaught were brought back to their vocation. Women had a key part to play.

Ordnance is the story of these men and women and traces the provision of equipment and armaments from raw material through manufacture to the supply routes which put into the hands of our soldiers all the materiel that they needed to win the war.

Dunkirk to D Day

The lives of some twenty men and one woman caught up in war. Most of the men served in two world wars, many came together on a course in 1922 (the Class of ’22) when enduring friendships and rivalries formed, some came later from careers in the industrial world. The woman would keep a faithful recorded of their deeds.

The story begins in Victorian south London. It goes out to Portuguese East Africa and then to Malaya, before being caught in the maelstrom of the Great War. Between the wars, its heroes work at Pilkington, Dunlop and English Steel; they serve in Gallipoli, Gibraltar and Malta; they transform the way a mechanised army is supplied. They retreat at Dunkirk – the army losing most of its equipment – and, by hook or crook, re-arm the defeated army. They supply in the desert and the jungle. They build massive depots, and relationships with motor companies here and in the USA. They successfully supply the the greatest seaborne invasion ever undertaken: D-Day. After the war they work for companies driving the post-war economy: Vickers, Dunlop and Rootes. Many died, exhausted, years before their time.

These three books started an itch; I was impressed by all the British companies which had risen to the demands of war and I needed to find where they had come from. This grew into a much broader quest which has resulted in.

I was also delighted to be asked to write the story of the MacRoberts Reply.

It is a story that has been told in fragments, but, when taken as a whole, becomes truly remarkable.

It begins in Aberdeen where a young Alexander MacRobert sets out for India to seek his fortune. His success comes in the shape of the British India Corporation. Mac, as he is known, meets a young American, Rachel, from New England. She becomes his second wife and they have three sons. In 1922 Mac is created Baronet of Cawnpore and Cromar. Later that year he dies. The eldest son, Alastair aged ten, succeeds to the title.

Tragedy strikes a further three times as each son is killed, the latter two in the service of the RAF. Rachel gives them the means by which they can Reply, in the form of a Stirling Bomber which she hands to 15 Squadron.

The Bomber, call sign F for Freddie, is piloted first by Peter Boggis, who would make his career in the RAF, and then by ‘Red’ King. The first MacRobert flew many operations but ended its day in a collision on the ground.

The MacRobert crest was transferred to another Stirling and this crashed tragically in Denmark killing eight crew members. The crash is remembered to this day by local Danish people who wished to show their thanks to the British bomber crew for supporting them in resisting the German occupation.

Radio operator, Don Jeffs, miraculously survived and spend his war as a PoW before undertaking and surviving the Long March home.

The MacRobert’s Reply name was revived in 1982 by Peter Boggis and since then XV Squadron has always flown a MacRobert’s Reply F for Freddie.

Find out more about the book which has now been published on Amazon

Charlotte Brontë’s Devotee

Completely different was my biography of my great great uncle William Smith Williams who discovered Charlotte Brontë.

“The mysterious publisher William Smith Williams has always been the unsung hero of the Brontë Story. Not only did he discover Jane Eyre, he was Charlotte Brontë’s friend and supporter. In a fascinating book Smith Williams is at last brought to life thanks to the forensic skills of his great, great nephew.” Rebecca Fraser

The book tells the revealing story of Charlotte Brontë’s relationship with William Smith Williams who, as the Reader at her publisher Smith, Elder & Co, recognised her genius. But, who was he? William was a radical Victorian, friend to many of the giants of 19th century art and literature: Thackeray, Thomas Carlyle, Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot and the Rossettis. Through him we gain an insight into the world of publishing, the art and science of lithography and the controversial thinking of John Ruskin on women’s education, politics and economics. He was a family man and, with his wife Margaret, produced a line of remarkable progeny.

Whence had he come and wither did he go? Charles Dickens and George Meredith were also publishers’ Readers and their stories are well known, but what of William Smith Williams?

I was spurred on my quest by words from a letter his brother in law, Robert Hill, wrote on his death: ‘There were complementary notices of his death in nearly all the papers. Nobody could have been more universally beloved or respected than he was.’ I read the obituaries and they were indeed full of praise and affection. One sentence in the Publishers Circular in particular caught my attention: ‘The truth is that Mr Williams’ previous education had fitted him to be a judge of good work, and he was singularly fair and unbiased.’ I had to discover what this ‘previous education’ had been, but also what else he had done to merit such fulsome praise and, indeed, who were those people who loved and respected him.

I found a true Renaissance man as at home with art as with literature, with science as with politics. His childhood had been spent in the crowded courts bordering London’s Strand. He was orphaned at age fourteen and then largely self educated. He was an apprentice publisher and then a lithographer before joining Smith, Elder. He wrote a poem in praise of John Keats and presented a paper to the Society of Arts on Lithography. Following his all too few years of friendship with Charlotte Bronte, he mentored many other writers. One such, Frederick Wicks, wrote this if him:

‘Thrusting back his massive growth of white hair, he would clasp his hands nervously in thought before delivering his opinion, and then would follow in short, pregnant sentences a perfect flood of light upon the matter in hand. He was never content with general commendation and approval, but always gave good, sound reasons and sufficient cause for all he thought. Among the many pregnant phrases that fell to my lot was one of extraordinary value as a check to the exuberance of youth. “You need,” he said, “restraint – not that which checks, but that which guides the literary faculty.”’

He edited the 1861 Selections of the Writings of John Ruskin and then supported Ruskin in the publication of his works on political economy. He is buried in Kensal Green cemetery with his wife, one son and two daughters and son in law celebrated portrait painter, Cato Lowes Dickinson under a memorial designed by AC Gill. His daughter, Anna, was a celebrated concert soprano. One grandson, Sir Arthur Lowes Dickinson, was a founding partner of Price Waterhouse in the USA, another, Goldie Lowes Dickinson, was one of the thinkers behind the League of Nations.