The world is facing multiple crises and politicians are scrambling for short term solutions. We live in a short term world. So many commercial and infrastructure assets are now owned by asset managers whose sole purpose is to achieve competitive returns for their investors, and, of course, themselves. In the UK, company law doesn’t help, for directors owe their duty only to shareholders who have power to reward or dismiss. Governments also seem more and more concerned with re-election, forgetting policies let alone anything resembling the common good or long term.

So many options seem to be binary. Electric cars are vastly better for the path to net zero than the internal combustion engine. Yet, batteries consume rare minerals whose mining is both environmentally damaging and abusive to those fellow human beings working the mines. That is aside from the sources of electricity for those cars which may well be from gas or even coal powered generation. Hydrogen may well be the better alternative, yet that argument also seems to revolve round the short term interests of those involved.

Energy more broadly offers an unbearable conundrum. We don’t want to take oil or gas from Russia and so have turned back to the Middle East and their oppressive regimes. There is still gas and oil under the North Sea; should those reserves be exploited as a third politically more acceptable alternative? The answer would seem to be no; not if net zero is to be achieved.

Kate Raworth, in her book Doughnut Economics – Seven ways to think like a 21st century economist, offers at a more conceptual level a possible way forward through these conundrums.

Growth in national income has been the mantra ever since it was first measured back in the thirties. As an accountant I can understand the attraction of having as your mantra something you can measure; for if you can measure it, you can compare it, produce graphs – the possibilities are endless.

Raworth offers this fiery retort:

‘Growth is one of the stupidest purposes ever invented by any culture,’ Donella Meadows declared in the late 1990s; ‘we’ve got to have an enough.’ In response to the constant call for more growth, she argued, we should always ask: ‘growth of what, and why, and for whom, and who pays the cost, and how long can it last, and what’s the cost to the planet, and how much is enough?’

Raworth traces arguments over political economy in recent centuries and comes across one of my heroes, John Ruskin, whose writings on political economy were published by my great-great uncle William Smith Williams at Smith Elder. Ruskin’s agonising over the questionable benefit of industry was derided. Have we come to reap its rewards?

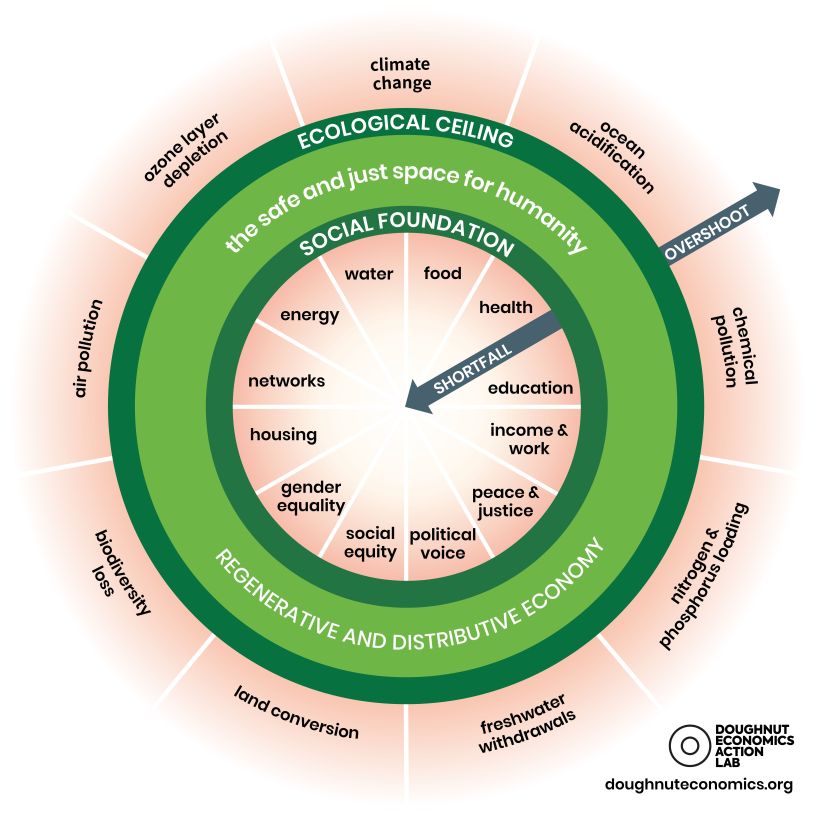

I have written elsewhere about the elephants in the manufacturing room, those subjects that we would rather skirt round. Perhaps the time has come to confront them and Raworth offers her image of the doughnut to enable that discussion.

I paraphrase, for which I seek indulgence. The doughnut is where humanity can live sustainably. It has a circle contained within it and a further, larger ring on the exterior. These are the constraints. The external constraints are those of the capacity of the planet to sustain life; the inner constraints are those in and among humanity: the overarching need for fairness irrespective of the accidents of birth. Raworth suggests that the aim of society should be to ensure that we all live within the doughnut, neither over-exploiting the planet nor treating some of its citizens unfairly. In that way the resources of the planet are both shared and sustained.

The featured image:

- Title: The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries.

- Credit: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier. CC-BY-SA 4.0

- Citation: Raworth, K. (2017), Doughnut Economics: seven ways to think like a 21st century economist. London: Penguin Random House.